[First published in 2008.]

Jiu-jitsu to the limit

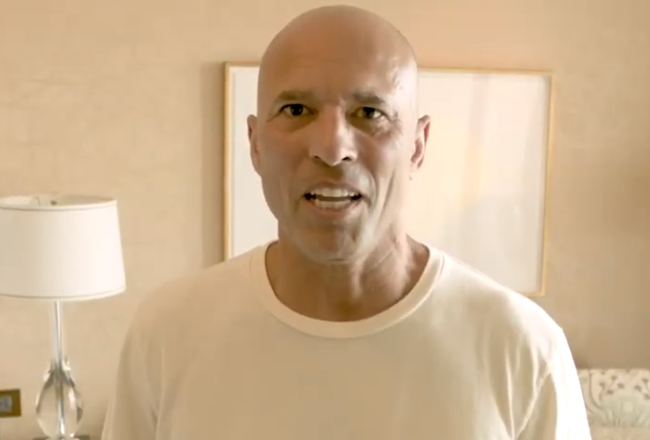

Celebrating ten years of his MMA career, Rodrigo Minotauro passes on to readers the best of what he’s learned in using jiu-jitsu to escape from the stickiest of situations

It’s the end of yet another grueling training day, Antonio Rodrigo “Minotauro” Nogueira’s unforgiving routine. In an effort to shed seven kilos, weight he gained to face behemoth Tim Sylvia in February, Rodrigo, 32, swims a few laps in the pool of his building on Barra’s beachfront, in Rio. At one in the morning.

And when a lighting bolt cuts through the drizzling sky followed by a deafening boom, in a flash, the Brazilian of 1.91 m and 114 kg darts to the edge and leaps far from the pool, with the nimbleness that won him millions of fans and crowned him as one of the most loved fighters in MMA, nearly unanimous in the fight world. Still laughing from shock, Minota changes tactics: he goes for a steam in the sauna.

Rodrigo has never been afraid of anything. All set to face Frank Mir, his rival on the Ultimate Fighter reality show, he hopes to win and face off against the colossal Brock Lesnar. He’ll take some hard knocks, most likely, as he’s grown accustomed to taking his whole life, since he was small. “Back home, even Mom got me and Rogério mixed up. When one caused trouble, it wasn’t uncommon for the other to take a licking, without a clue what was going on,” the UFC heavyweight recalls. The delights of having a twin brother…

But Minotauro was more of a menace than his bro Rogério, another MMA star in Japan and the USA. Folkloric, in the town of Vitória da Conquista, Bahia, are the deeds from Rodrigo’s childhood: a fight with 12 in front of a Catholic school, a brick to the head as a gift from a rival group, a number of altercations brought on by the nickname he hated: “Fatty.”

Besides being a big eater, he was valiant, but it was all instinct. He practiced judo since 4 years of age, was competitive to the extreme, one of those kids who gushed tears when he lost. The art of dominating, falling and getting back up, though, was not enough to put a damper on little Nogueira’s impetus.

Not until the 15th of August, 1987, when Rodrigo faced his greatest trial. In front of his uncle Elpídio’s house, the 11-year-old boy played with the other kids hanging from the back of the truck of Jubervaldo Louzada, an old friend of the family. Amid the hullabaloo, they didn’t see the truck was about to take off from the party for the high road. While the vehicle backed down the hill, Rodrigo let go of his hold on it and fell. With his back to the ground, as he has become accustomed to fighting, he had only enough time to move his head out of the way, and the tire rolled over his body and one of his legs. Unable to imagine his leg had been crushed, liver split, diaphragm and lungs perforated from the back, the young Minotauro ignored the pain and got to his feet. And he implored Rogério: “I’m fine; don’t tell Mom!”

The battle against death was not an easy one, entailing four days of coma, and extremely costly and extensive surgeries and treatments. One of the doctors to follow his case in Salvador, the well-respected Dr. Bahia, has the explanation for Rodrigo surviving on the tip of his tongue: “It was a divine miracle.”

Throughout his MMA career, which began when then-boxer Rodrigo watched tapes of Rickson Gracie fighting, Minota was the protagonist in what many fans see as being small miracles. After all, after facing the biggest (enormous) tough guys of the rings, Rodrigo counts 31 wins in 37 fights, with 19 submissions, several of which are epic. There are nine different armbars, four triangles, two anaconda chokes, one crucifix, one rear-naked choke, one kata-gatame (arm-and-neck choke) and one guillotine, which Tim Sylvia was the beneficiary of.

Some call them miracles. Rodrigo calls it jiu-jitsu. “I’m a fighter who has always had a standup game, but my lifesaver will always be jiu-jitsu,” he tells GRACIEMAG, which trailed the star for three days, to bring readers useful lessons, not just for competitors, but for common practitioners and admirers of a fighter with such a peculiar style.

If specialists regard BJJ as the art of making the opponent as uncomfortable as possible while making oneself comfortable, Rodrigo’s jiu-jitsu seems to be quite the other way around. It’s the adversary who feels in a comfort zone, dealing the cards. And when he comes around, he ends up twisted out of shape and trapped in one of Minotauro’s trademark holds. Why does this happen? Rodrigo tries to explain it in the interview held at two in the morning to come. Quite an ordeal.

Q: In the book The Art of War, Sun Tzu says: “Those prepared for confrontation establish a situation in which they may not be overcome, and do not miss the opportunity to defeat their opponents.” In another excerpt, he states: “Not for being honored for intelligence, or credited with heroism – they win because they make no mistakes.” Do you make mistakes, Rodrigo? Is that how you learned to fight under pressure?

A: It happens that I’ve fought against some complicated guys. Give me a can and I’ll finish him quick! Most of my adversaries aren’t cans, so I have to get the guy to open up, and part of the tactic is to take calculated risks. But I make mistakes sometimes, both in tactics as well as wanting to stand and trade a bit too much. But that’s because I feel comfortable. I’ve practiced boxing for over 15 years, and I’m unworried, in finding the right time to take it to the ground. I prefer that to sticking to the guy like a madman, exerting force to take the guy down. Once on the ground, I seek to not miss any opportunities. That is when you can’t make any mistakes, and I do feel I make few mistakes.

How do you sharpen your game to not miss any chances, spot openings and learn to have a good counter-attack?

The best way is to compete in BJJ. Championships were fundamental in my career. By fighting, you become thick-skinned, gain instinct and experience to change tactics under pressure, before or during the fight. In the gi, you don’t know who your next adversary will be; you encounter new moves and less conventional games, so you learn not to be surprised.

Those who compete also gain technical savvy and fine-tuning on the ground. I’m impressed by the skills of the folks who show up at my academies in Miami and Dallas. They know BJJ; they know positions that surprise me. But the guys don’t have any fine-tuning. It’s by competing in the gi that you understand what it is to score two points and have to breathe and hold the position, or make it to the back and not leave it till you win the fight. Anyone who has been through that, from blue to black belt, misses a lot less positions in the ring.

You were champion at weight and in the absolute at the 1999 Pan-American, as a brown belt, with expressive wins over Givanildo Santana and Ricardo “Cachorrão” Almeida. Now, as a black belt, at the Worlds the same year, you lost after an epic 4 to 4 score against Roleta. Is winning a championship like winning an MMA bout?

It is; you leave a championship in tatters. On the psychological side, competing also strengthens your mind and makes fighters become accustomed to pressure. After facing the crowd and rivals in the gi, you control the adrenaline better in MMA.

Can one “learn” to be a durable athlete, with the heart to get out of sticky situations?

I don’t believe one has to go through what I did in life, like getting run over and all, to be a warrior. It comes from the heart, it’s the person’s vocation; each has their own inspiration. The trick is to be well trained and confident in one’s game plan. Doubt is what undoes a fighter.

Being durable comes about from being in good shape too. I always swam, did judo, I liked waking up early in the morning to row, to box in the afternoon and do BJJ at night.

And technically, how does one train to surprise their opponent?

That’s my style, isn’t it? When the guy thinks he’s comfortable, that’s when the walls come down. That comes down to training; I like to put myself in uncomfortable situations – in training. I like testing myself, training under pressure. If Rogério catches my leg and is about to take me down, sometimes I let myself fall: let’s see what I learn here in this “crappy position.” I don’t fight to win in training. If I have to take a punch to the face from Vítor Belfort, I make the most of it to derive some lessons. In a tight situation, I’m learning. If someone wants to always win in training, when the heat is on in the fight they won’t have much experience or instinct to see a way out.

I also seek, for every fight, to bring in new sparring partners, of different sizes and skill sets. Always training with the same partners makes your training played out. And you end up paying for it in the ring. It’s vital that one goes into the fight with a plan A and plan B.

How do you program body and mind for when the going gets tough?

It doesn’t help to be hyper-trained and your head not be connected to the person you’re going to face. We’re young, and when you start making money, options start popping up, but it’s vital that you hold back. It’s worthwhile to take the last week to concentrate on the fight, to be alone, to be away from friends, to watch fights and get in the mood. I imagine myself shaking my opponent’s hand, I visualize the fight, and I start getting used to the idea of what is to come and anticipate the action, to avoid surprises.

What is your limit?

I’ve sparred for an hour and five minutes with Anderson Silva, some 13 rounds. In the gi, I’d do three rolls of a half hour each nonstop. My stamina can’t let me down when the time comes. These days, the training that demands the most of me is physical conditioning, weight-lifting sets of five minutes, the duration of a round in the UFC, led by Romanian Dragos Doru Stanica. I get sick, dizzy, and Dragos laughs. As the legend goes, he was from the circus and made it into the “Guinness Book,” for supporting eight people on his head. He’s a hard core tough guy.

Have you ever done anything you regret in the ring?

I have, when I had too much heart and not enough maturity. My regret in my career was having taken my first fight with Fedor (loss by unanimous decision), in 2003. I was really injured, with a seriously herniated disc. It’s stupid to not respect your body’s limitations. These days I wouldn’t do that, nor would I let anyone on Minotauro Team do it.

Who has given you the hardest time in training on the ground, Rodrigo?

Allan Góes, a monster. He’d give everyone at BTT a hard time.

In MMA, you started from the bottom, right?

I became a professional early on. At 22 my daughter was born, I had to pay rent. In my first fight, in June of 1999, against David Dodd, I made 150 dollars. The car broke down on the way, I paid for the hotel, ended up spending 300 dollars to fight, when all was said and done. The guy promised me a thousand dollars, but when it came down to it could only afford 150. And I found that out right at that moment, with the guy already lumbering towards me, with 104 kg of lean mass, me much lighter. What a predicament, I thought to myself. But I remembered a karate teacher in Miami, where I lived, who promised me a place to teach BJJ if I won my fight. So I fought to win a job.

But in BJJ, I also had a rough start. In my first training session, in 1994 at the academy of Guilherme Assad, I was submitted twice by a blue belt 30kg lighter than me, Ricardo Gatomé.

How long did you train for your debut?

I had been training MMA for four months, as a sparring partner for Marcus “Conan” Silveira. And my adversary was coming off a submission win over Jeff Monson. The fight started and he came out hitting me in the face and slammed me down. I pulled half-guard, tried for an omoplata, until Luis Bebeo Duarte, who was in the USA and was my cornerman, yelled: “This isn’t jiu-jitsu, kid! This is the real deal!” I learned by practice. But in the tangle our technical superiority ends up showing through: I sunk a crucifix and grabbed his neck. That was a decade ago. But in 2009 it also makes ten years since I conquered my black belt, my most important belt.

When has BJJ surprised you in a fight?

In most of my fights the submissions comes about and I don’t even know how. The thing is to practice a lot of repetitions, for BJJ to come automatically.

How has BJJ helped you in day-to-day life?

Training is a moment of meditation. When you’re having your neck squeezed, you detach from everything, you forget your problems, the bills to pay. BJJ is great therapy, and it works for everyone.

How do you assess yourself as a fighter?

I’m a tough guy, I have durability and heart, but overall I think there are a lot of aspects yet to improve on, especially my explosiveness and flexibility. I’m reasonably good on the ground, but with every training session I learn something new. In jiu-jitsu, you’re always learning.