Exactly one month from the big day, Brazilian fans eagerly and enthusiastically await August 27, the day of the UFC’s return to Brazil, in Rio de Janeiro . Do you remember how the first Ultimate Fighting Championship in Brazil went? What went through your mind that night? Revisit the occasion here on GRACIEMAG.com in an article penned by Rafael Quintanilha, originally published in NOCAUTE magazine to honor the ten-year anniversary of the event, in 2008.

Frank Shamrock, Pedro Rizzo, Ebenézer Braga, Jeremy Horn, Tank Abbott, Pat Miletich, Vitor Belfort, Wanderlei Silva – those were the big-name fighters who, that night of October 16, 1998, set foot in the octagon in São Paulo City for UFC Brazil, in one of the biggest, if not the biggest, MMA events ever held in Brazilian territory.

It’s true that the Ultimate Fighting Championship was not the major worldwide promotion it is today but it’s not every day that Brazilian locals get the chance to witness two title fights in the sport’s pioneer organization at Portuguesa gymnasium (packed with 6,000 spectators), see Pedro Rizzo make his debut in the event that launched him to fame, much less watch two of the biggest Brazilian stars of all times go toe to toe with each other – a situation where pretty much anything can happen (and really quickly).

But why did the Ultimate Fighting Championship set up shop in Brazil? Obviously, ever since Royce Gracie first made it big, Brazil has been a breeding ground for MMA talent; but the trip south of the equator also came down to necessity. It happened that, in 1998, MMA was prohibited in much of the United States.

The UFC came into existence as a series of practically ruleless brawls organized into a tournament format. The event was a major success in pay-per-view sales from the outset; but when Senator John McCain – yup, him – saw the recordings of the early tournaments, he took the forefront in a campaign to ban what he called “human cock-fighting” from the United States of America, sending letters requesting the prohibition of such events to every lawmaker in the country.

Thirty-six of 50 states followed suit – even New York, enacting the ban on the eve of UFC 12, obliging the promotion to hastily move the event to Dothan, Alabama, where the show went down on February 7, 1997. With a dearth of places to hold the spectacles at home, in 1997 the Ultimate Fighting Championship made its way to Asia, where UFC Japan 1 took place. In 1998, between UFC 17 and 19, it was UFC Brazil’s turn.

Already renowned for his work promoting International Vale-Tudo Championship (IVC) and on close terms with the UFC, Sergio Batarelli was contacted by Bob Meyorwitch, then the president of SEC, the Ultimate Fighting Championship’s holding company.

“He [Meyorwitz] knew production and filming costs would be cheaper in Brazil, and, as there were a number of Brazilians making waves at the time, they came,” recounts Batarelli, who rolled up his sleeves and got to work to make the show happen: “They had a filming deal in place with Globosat; the lights they brought with them, and the company doing the lighting was theirs. I did the rest: ticketing, publicity, security, we had a top-notch referee from the CBVT (organization that sanctioned the event). We worked as a team. I even changed some of the rules in Brazil, as I felt they weren’t fair to the fighters. I banned wrestling boots here, and as time went by they were banned once and for all.”

Matchmaking

For UFC Brazil, the Ultimate Fighting Championship already had some ready-made matchups, but being in MMA’s birthplace, it was fitting to bring in some up-and-coming local talent. “Belfort vs. Wanderlei was my idea, Ebenézer vs. Jeremy Horn too, as were the prelims between Brazilians,” says Batarelli. But if Batarelli hit the nail on the head with the Brazilian first-timers he stuck on the card, then-UFC matchmaker John Peretti did a fine job of his own, as Pedro Rizzo recounts: “At the time I was living at Marco Ruas’s place in the United States and had some wins at the IVC under my belt. Marco taught in Beverly Hills, where Mark Kerr and Bas Rutten used to train and where Peretti was always around. Peretti knew me from there, and he’s the one who first contacted me to participate at UFC Brazil.”

According to Batarelli, one of the promotion’s concerns was security – images of the pandemonium in the stands at Pentagon Combat one year earlier had made it around the world, despite it taking place one year earlier and in a different city. “They wanted lots of security and the works, and I told them I’d show them we could control everything no problem, that if the fights were good and went according to schedule, we’d have no problem,” remembers the promoter. “And we did, and there wasn’t even a divider separating the crowd from the octagon; everything went smoothly. The only threat was when Wanderlei was knocked out and [José] Pelé invaded the octagon. Things got a little tense, but I personally went to talk to Pelé and Rudimar [Fedrigo], and everything cooled down.”

Following the preliminaries with César Marsucci and Túlio Palhares, who overcame Paulo and Adriano Santos, respectively, it was Ebenézer Braga who kicked off the main card, facing Jeremy Horn. Ebenézer had a respectable 16w-3l record and was making his UFC debut. His opponent, Jeremy Horn, at the time already exhibited the tendency that makes him one of the sport’s most prolific athletes (then holding a record of 12w, 3l, 3d; today he has a ludicrous 112 fights to his name at just 33 years of age).

Horn made his UFC debut losing to Frank Shamrock, the middleweight champion, and although he’s shown himself to be an extremely confident fighter throughout his career, he left the Brazilian octagon with his second loss in a row in the UFC. Ebenézer scored a takedown three minutes into the fight. Horn defended and replied in kind with a double-leg. But he left his neck exposed and the Brazilian made a meal of it – a guillotine with 3:28 minutes on the clock. Besides it being a stellar display from Ebenézer, the fight warmed the crowd up for another Brazilian-American showdown to come later in the card.

In the heavyweight bout, Pete Williams went on the attack but was unable to bring a definitive finish to the fight.

TK pursues the belt

As announced by the UFC Brazil commentators, Randy “The Natural” Couture decided not to defend his heavyweight title, leaving the post vacant. This opened the way for Pete Williams and Tsuyoshi Kohsaka to face off in the octagon for the belt. Unfortunately, the 15-minute fight went by without much of anything going on. TK spent a good chunk of the time trying to sink a kimura, but to no avail. Williams did manage to make it to mount and, near the end, land a high kick that wobbled the Japanese fighter – too little too late, though, and the outcome was left in the hands of the judges, who awarded the unanimous decision win to the Asian fighter.

The very first lightweight champion

If the previous fight didn’t get a rise out of the crowd, how about the second one? After beating Eugênio Tadeu in his octagon debut, Mikey Burnett was set up to fight for the title of the first-ever lightweight champion (a weight division equivalent to the welterweight division of today) against Pat Miletich, already a legend at the time, making his 24th professional appearance. Burnett did try to get things moving in the match but Miletich spent a good part of 21 minutes pulling on his shorts. Burnett managed to land a few takedowns, to which Miletich responded by using his commendable guard not to take any damage.

The fight over, Miletich took a controversial unanimous decision and the belt with it. Burnett would next fight at UFC 18, in 1999, and then take an extended hiatus, only to return to MMA in the fourth season of the Ultimate Fighter reality show.

Rizzo takes on the barroom brawler

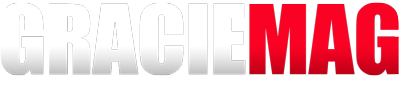

Returning some of the crowd’s cheer, Pedro Rizzo vs. David “Tank” Abbott was a barn burner. Not only did it mark a Brazilian’s octagon debut but it put a bona fide MMA icon on the Ultimate Brazil stage. Rizzo recalls the events that make up one of the most memorable nights of his career. “There’s always a lot of pressure when you fight in Brazil, regardless of how they say it’s great to fight at home,” says the Rio de Janeiro native. “It was all nuts. First Royce had that marvelous campaign of his; then Marco Ruas came in and started winning everything; Vitor also came in winning everything, but no one ever imagined there would be a UFC here. And nobody really believed it when they said there would be one, even though the promotion wasn’t as big as it is today. MMA was at a standstill.”

The match was made and Rizzo went to work training to take on the famed street fighter. “I think everyone thought he was going to knock me out,” says Rizzo. “He’s a brawler, but he’s not technical. He weighed 150kg and hit hard – if you watch UFC 6, he got two horrifying knockouts [on John Matua and Paul Varelans] that crumpled the guys. He hit really hard, that’s what garnered him respect. He was never a great fighter, he was always a barroom brawler; but at the time not a lot of people did MMA, and the crowd ate it up. UFC fights lasted one 12-minute round with three minutes of overtime. So I decided I had to move around a lot in front of the fatty. So I started kicking his legs, and he started wearing out. Then I started using my hands till the knockout came around.” Alas, the final combination of strikes was so violent that, besides putting the American’s lights out at 8:07 minutes, it caused him to drop MMA for pro wrestling, only returning five years later.

Knocked out, sure. Sober, no way!

Anyone who thinks a brutal thrashing means the end of a fighter’s night, doesn’t know Tank Abbott. Queried as to the most peculiar stories to come out of UFC Brazil, Sergio Batarelli doesn’t beat around the bush when it comes to his favorite. “After the event, there was Tank at a watering hole on Augusta Road guzzling beer, his face all messed up, and surrounded by ugly women,” remembers the promoter.

The day Wand didn’t debut

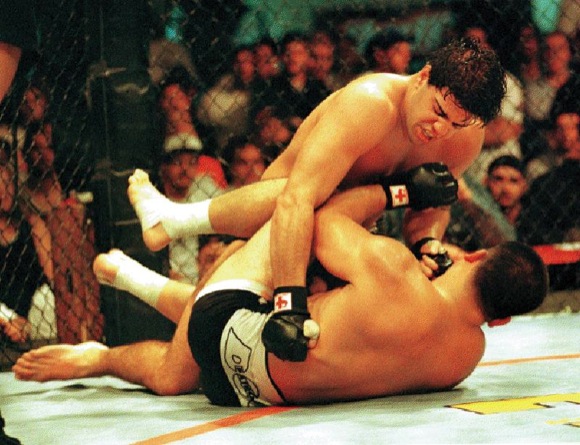

“It was a really sad night,” is the simple and sincere synthesis of that October 16 evening, according to Rudimar Fedrigo, the leader of team Chute Boxe. Despite the fame the young Vitor Belfort enjoyed at the time, Chute Boxe was taken by surprise with the knockout suffered by Wanderlei, who had already begun to show the qualities that would make him a legend of the sport.

“Everyone including me thought Wanderlei would win by knockout,” says Batarelli. “But the great part of the sport happened – prognostics don’t count, getting your fist in there first does. Vitor dished out a deadly and perfect combination and shut up a lot of people. Wanderlei was knocking everybody out in the IVC, even the foreigners, and the owner of the Ultimate Fighting Championship himself felt he’d win. If Vitor had lost, perhaps his purse price would have gone down some.”

Curiously, Belfort almost didn’t make it to the octagon for one of his greatest performances. “Before the event began, the owner of the UFC came to me and said he was having problems with Vitor, who was saying he wasn’t feeling well and didn’t want to fight,” recalls Batarelli. “I went to speak with Carlson [Gracie] and Vitor’s mom, and after a slightly stressful situation he calmed down and got in the octagon for a brilliant and stunning performance.”

This time on the wrong side of a brutal knockout, Wanderlei succumbed to his aggressor after just 44 seconds of fighting. To the man who silenced the gymnasium – and dropped weight divisions two fights later after being knocked out by Randy Couture –, there’s only one explanation for such an historic knockout. “Training a lot and fighting,” said Belfort in summary.

Everyone knows the giant Wanderlei would become in the years that followed, but one can imagine how that night, still unknowing of the idol he would later become in Japan, was no small frustration for Wand. “What bugged Wanderlei wasn’t that he lost but that he didn’t get to do anything, that he didn’t get to show his potential,” says Rudimar, the partner who consoled Wand on the bus Chute Boxe rented to take them back to Curitiba.

Shamrock and revenge

Wrapping up the event, Frank Shamrock would defend his middleweight belt against another UFC first-timer – John Lober, who happened to have beat him at Super Brawl 3, in January 1997. But this time the story went differently. Lober spent a good while in the uncomfortable position of having to defend his neck from a guillotine. Unable to finish, Shamrock opted to stand and brutalize his opponent by hacking at his legs with kicks. Now Lober’s attempt to return in kind didn’t turn out so well, as he took a straight right to the face that laid him out on the canvas. Again on his feet, Shamrock dropped Lober for the last time with knees, and this time he followed him to the ground to finish the business – taking a ground-and-pound onslaught against the fencing, Lober gave up at 7:40 minutes. Shamrock kept his belt.

Forgotten octagon

“Something interesting that happened is that they left the octagon at a storage facility at Santos Port,” says Batarelli. “A few years later they called me asking what I wanted to do with it. I didn’t even know; it was all rotten, so I left it there.” From the look of it the UFC didn’t leave its traditional stage there with the intention of returning. It’s a good thing they changed their minds.