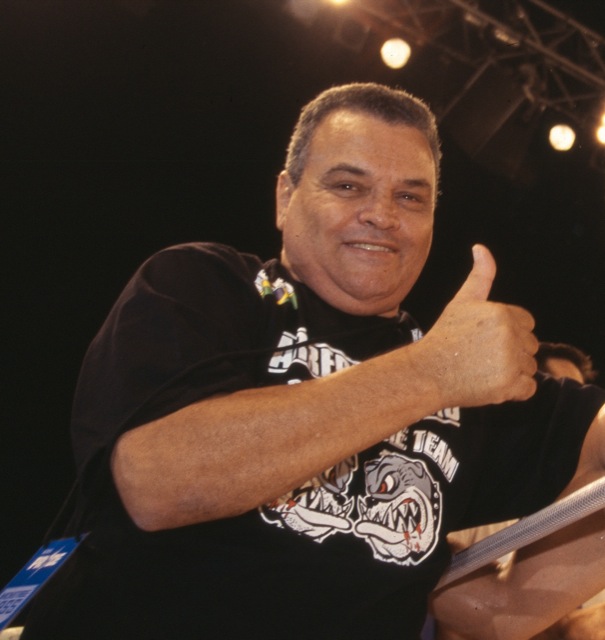

Grandmaster Carlson ringside in Japan, in a striking photo by Susumu Nagao. Photo: Archives, GRACIEMAG

Carlson Gracie was born on August 13, 1933, but celebrated his birthdays on the twelth to be safe. In fact, he was not born Carlson, but Eduardo. A few weeks later Grandmaster Carlos Gracie decided that his first child should have a stronger name with the letters C and R – a tradition that started with Carlson and would go on to be a mark of the family. On the day the red-belt who died in 2006 would have turned 80, GRACIEMAG recalls some episodes involving the teacher who changed the face of Jiu-Jitsu, through the text of one of his most loyal black-belts, Vinicius Cruz. Happy reading, and thanks, Carlson.

*****

Think of a unique guy: that was Carlson Gracie.

He did not give a damn about money and made no distinction of people based on status. His sincerity was rough, bordering on rudeness, whether he was with a beggar or the president. That was Carlson.

I had the opportunity to know him as a boy and always had the dream to wear that kids’ gi that read ‘Carlson Gracie Jiu-Jitsu’ on the back. And, when classes at the gym of teacher Manimal began to run too late, I saw the opportunity to make that dream become reality.

I’ll tell you something that those who experienced it will have to agree on: when you went Carlson, you did not go back! Yes, Carlson was addictive.

There’d always be injured fighters, which were not few, that went to the gym just to be on the sofa in the sitting room, to get the chance to listen to Carlson grumble when someone abandoned a kimura to do anything else – he loved the kimura.

Or they’d go there to take a ‘hawk paw’ to the top of the head (Carlson joined fingers and slapped your head with his fingertips) when you dared say someone deserved to move up in belt. Incidentally, if you wanted to see a guy languish in his current belt, all it took was telling Carlson that the guy was tough and deserved to be promoted. You’d earn yourself a hawk paw, you’d get called a belt pimp, and the poor guy, who had no fault in the matter, would get a few more years at that same belt.

More often, however, we’d go just to be ruthlessly teased when he decided to play dictation with the class that was packing the room. He’d pull his notebook from his pocket and you’d get called a dumbass as soon as you spelled something wrong.

And I laughed my ass off.

It seems strange, but anyway … Commoners in the presence of the greatest of all, and he was there as one of us, always. I remember a time when I was in the lounge and he ordered: ‘Vinicinho, grab a paper and a pen.’

I got from uncle Amauryzão, father of Amaury Bitetti, a pen to start the dictation. Then he, with that air of someone who wanted to mess with me, said: ‘Write the name of that little bone at the end of the spine, the coccyx …’

I luckily knew and wrote right; amazed, he cried, with his peculiar sincerity: ‘Eeh! This one didn’t cut class then! ‘

Carlson was so unique that while people dreamed of a new car, or something like that, he spent all his money buying CDs, cassettes or taking his students to the steakhouse. And the gift that gave him the most joy was a simple whirligig. I swear. He was like a child, playing with that thing for hours.

When guys like that go away they always leave their mark. Indelible.

Carlson would create a slang, or bring a word from the cockfighting scene to the Jiu-Jitsu milieu, and voila! In a month the word was already on everyone’s lips. What Brazilian fighter hasn’t heard someone be called a ‘creonte’ or ‘mutuca’? These are words that transcended the boundaries of the gym and are now used by fighters of every martial art in the country. Not to mention his ‘dictionary game’ and the world-renowned ‘powerfulness test.’

It was not just that intrinsic shine he carried in his soul that made him unique. His brilliance as a teacher, and especially as a coach, were unparalleled. Carlson had a keen eye. He was able to unveil a position, one which for us was mind-bending, in two or three simple moves.

I often saw my idols studying positions (yes, I had the privilege of sharing the mat with my idols and become great friends with them), and Carlson would come and say: ‘Do this and that …’ and he’d find a quick and simple defense to a position which until a few moments ago looked indefensible. In competitions, it was almost a ritual to finish our fights and go hug him, whether he was one of the organizers, or in the stands, where he liked to stay on the edge, leaning with his arms hanging. And when Carlson was watching you’d fight harder.

I also saw, many times, on Figueiredo Magalhães street where qualifiers were held for competitions, that two guys would start fighting in the dojo and then go to the bathroom to finish up. No one liked to lose in front of the old master.

I remember it all with a tightness in the chest, and I say without a second thought, it was the best time of my life. I’d get there in the morning and find Carlson Gracie Jr. teaching class. In the afternoon, I’d be sitting on the bench at the 3 p.m. class, just to get scolded by black belt Marcelo Alonso. Sounds crazy, but I liked to take Alonso’s scolding; I did not know him very well yet, and this was his way of knowing that I existed.

Then later in the evening I’d take the class of teacher Saporito, always full of champions (Luiz Sergio Barros, Daniel Christoph, Paulão Filho, Maurício Cobrinha Azul, Pedro Babu, Dudu Barros, Bernardo Zuza, Zé Emilio, Daniel Cardoso and many others). And finally, I’d relish free practice, on the delicious right-side mat, when I’d find Murilo, Amaury, Bebeo, Libório, Parrumpinha, Wallid, Allan Góes, Rogério Miranda, Marcel Ferreira, Eduardo Lerner, Eduardo Lins, Alexandre Macedo, Sergio Abimehry and master Rosado – who appeared from time to time, squashed everyone and left – among many others.

The memory of the old master lives with us in every story, every workout. And to me, every time I go up those stairs on 414 Figueiredo Magalhães St., a movie plays in my head, of him telling me to listen to Edith Piaf, scolding me when he heard of any hijinks, or giving me a ride back to Morada do Sol… It’s all tattooed on me, and motivates me to teach what he taught me one day without even trying: Jiu-Jitsu deserves to be known by everyone, not just those who have money to pay.

I hope to be lying on the mats of life, always, until the divine laws do not allow me anymore, learning, teaching, and especially raising the flag of the biggest myth in the history of contemporary martial arts.