[First published in 2014. Scroll down for plain text.]

[ Marcelo Dunlop & Raphael Nogueira ]

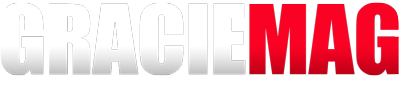

Becoming fluid

This fast-paced, relentless fighting style that leaves opponents at bay is now within your reach. That’s what unforgiving champions Ronaldo Jacaré and Flávio Canto teach next. Check it out!

GRACIEMAG: What does the nimble game mean to you? To not stop moving until an advantageous position is reached? To never quit?

FLÁVIO CANTO: In my opinion, there are two paths for ground training. One focuses on strong, efficient positions. The other, which I like most, is about “flowing.” This is the one that brings about the magic. I believe in the idea of developing skills to avoid having to choose the position. You flow and it arises at some point. I go for the arm and a choke appears; I go for a pin, then there’s a choke and then a lock. I never limit myself to a specific position. Regarding the time to stop flowing, I think it makes sense to refrain from it in certain moves, especially in the setting of certain positions. In these moments, the less your opponent moves, the better.

RONALDO JACARÉ: Since Jiu-Jitsu was the only thing I had in life, I think that was reflected on my game. I’d throw myself at the positions with real hunger. I’d try to pass five, ten, 15 times on the same side until the opponent gave. If he was still holding me back on the twentieth, I’d just change sides and he’d get completely disoriented. I think a seamless game is all about persistence. And it’s the fruit of tireless training. I’d do about six training sessions per day – I’d train, eat, sleep, wake up, train, sleep, wake up, eat, train…

Being nimble, then, is the art of accelerating one’s Jiu-Jitsu to leave the opponent trying to catch up on defense?

FLÁVIO CANTO: I have never trained thinking a lot about pure defense. I’ve always tried to turn every defensive position into one of attack immediately. I have never liked the idea of static ground play. The idea of the slow, chess-like match, (as in, “I made a move; now it’s your turn and so forth”) never made sense to me. When training guard-passing, for example, my mission is not to stop until I pass or, if it goes wrong, until I’m swept. And we take it from there. The pace should always be fast – always.

What is most important for the practitioner who wants to do the fluid game? Stamina, physical strength or mental endurance?

FLÁVIO CANTO: I think it’s a matter of culture. Even if you lose many positions in the beginning and have to expose yourself, it pays off to follow this path of fluidity. As I said earlier, that is what brings about the magic of the ground game. To arrive at the appropriate level to achieve this magic, it is also important to change the way you train. More important than the position itself is to practice skills, both with a partner and without one. Prepare for all kinds of situations. This only becomes intuitive after you repeat almost all combat situations many times over.

RONALDO JACARÉ: There is perhaps a myth that the fighter who likes the dynamic game works out, runs, circuit-trains all the time. I, for one, have never liked running. Back in Manaus I would just do brisk walks. Afterward I discovered that that burned my lactic acid and helped in my physical recovery to allow me to train more and more. I have always gained stamina by just practicing and doing the drills I learned throughout my career, like the ones I’ll be showing here. One suggestion that worked for me: I have never liked to do ten-minute rolls, which tend to stall at the end. I’d prefer to train for six minutes with different sparring partners at a much faster pace. The teammates would be always rested, of course. And I’d have to take them on under severe exhaustion.

What Jaca says brings up another question, that of training while tired. This can become a major barrier in Jiu-Jitsu, if practitioners insist on only training when they’re recovered from previous sessions. When they avoid training exhausted against a tough colleague, the athlete flees the muscle pain and cardiac demands inherent to a dynamic game. How can the teacher release the student from the shackles of avoiding to train exhausted?

FLÁVIO CANTO: In judo it is more common train tired and to not take the training score too seriously. This mindset is favorable as far as evolving. You train less concerned about errors, you risk more and in a way you evolve faster. I think the teacher should always encourage risk-taking, keeping in mind that training means risking new positions, new concepts – experimenting. Perhaps because Jiu-Jitsu training tends to be generally “looser,” there is more room for the athlete to rest a bit more before their next roll. This results in the athlete getting used to defining their physical and mental state before a session. And, again, training also means preparing for different sensations and physical states. Who’s to say if in a future competition you will find yourself in a similar situation during a fight? I think the teacher, at least in the training of competitive athletes, should demand that everyone follow the entire workout without rest. It is part of the mission of the coach to strengthen the spirit of the student, and that cannot be taught without good old suffering and the overcoming thereof.

One of the most admirable features of fluid-game experts has to do with the expression on their faces. It’s amazing how, in spite of making great physical effort, such fighters always keep a quiet countenance, which gradually undermines the opponent psychologically. The opponent starts thinking, “Doesn’t this guy get tired, my God!”

Just how important is it to know how to conceal one’s own exhaustion, and what are the tricks to this sort of acting?

FLÁVIO CANTO: I really believe in that. Two big names in Jiu-Jitsu come to my mind: Rickson Gracie and my friend Vitor “Shaolin” Ribeiro. I do not recall seeing them competing looking strained of suffering. Roger Gracie, ditto. In judo, Leandro Guilheiro has that trait. I’ve never stopped to think whether I fight like that – probably not. My way of training and fighting on the ground has always had much to do with what the rules of judo impose. I’ve never had more than a few seconds to win on the ground, lest the ref stop the fight and stand us back up. So I got used to training like that. This forced me to flow all the time and never stop in one position too long without shifting to something else. I’ve always had to show the ref I was going somewhere. I could only stop once I got a pin or a submission. During training the time to rest from all the position-shifting is while pinning your adversary. By the way it is possible, and sometimes desirable, to stop at that moment. I see athletes sometimes wanting to get the sub before adjusting the pin and they end up losing the position.

In a battle of one dynamic fighter versus another, what are the details that make one side come out ahead? Who wins: the fighter on top or the one on the bottom?

RONALDO JACARÉ: In general, at black belt, fighters playing on the bottom get more tired. Having your legs up, contracting the abdomen constantly, and still managing the opponent’s weight and the force of gravity… Anyway, I think all these elements pose a challenge to the guard player in the “dynamic vs. dynamic” battle. It is essential to never let the top opponent loose. I only fight on the bottom with my opponent’s sleeves dominated. I control the fight, I control his flowing and so I attack more and win, I think.

FLÁVIO CANTO: Me, I think that the culture is the same. In the case of the passer, the path is to not quit until they pass or get the sub; in the case of the guard player, the path is to not quit until they sweep and get the sub. If during this process something goes wrong – you get swept or get your guard passed, – pull yourself together and get back to the attack. If you can’t, then tap out and start all over again, with the same principles. That’s how I train. I believe in the case of “dynamic vs. dynamic” there is a constant struggle to see who is one step ahead. The winner is usually the one who takes two steps ahead and leaves their opponent unable to defend in time. I remember Leozinho Vieira was an athlete who’d shift between attacks the whole time and would usually succeed with that method.

Are there differences between standup nimbleness and ground nimbleness? What are the peculiarities of each type?

FLÁVIO CANTO: Those are different situations. I’d say standing, following the culture of attacking and always being one step ahead, it makes a big difference to keep ahead grip-wise. I always suggest that we should learn to fight alone. A good standup fight for me is one where the opponent never stands a chance. That one where you’re always one step ahead. Aurélio Miguel used to fight that way. In order to get to that level, it’s important to thoroughly practice how you approach your opponent’s gi.

What is the greatest piece of advice you have ever heard regarding your movements as a Jiu-Jitsu fighter?

FLÁVIO CANTO: I have had many influences. With my coach Geraldo Bernardes, I always had a balance between ground and standup. Two days of the week were more ground-focused, two more geared toward standup, and Fridays it was all mixed. I grew up understanding this division and understanding that it would be important to develop both parts and turn them into one. To this day the guys tease me. I’d always continue standup training on the ground. At the start I’d ask my partner: “Can we keep going?” I think nobody does this in judo. Maybe once or twice, but not all the time. Thus I ended up learning a lot about that invisible moment between standup and ground; I studied hard on what to do at that moment of transition. I had the privilege of learning a lot from Sensei Leopoldo De Lucca, one of the most special people I have met in my life, and to grow up learning from [physical coach] Paulo Caruso. I met Paulo when I was 16 years old and since then we have always been together. He’s taught me a lot and also he has the culture of constant attack in his game. When I see him training, even today, I realize how important he has been to me, and how similar my game is to his.

RONALDO JACARÉ: Everything I learned as a fighter was from Sensei Henrique Machado, in Manaus. However, some drills that I learned at Grandmaster Osvaldo Alves’s gym have helped me a great deal too. I would do 20 reps of each every day. But I think physical and technical exercises are not enough. You must have the warrior’s spirit. If you go in scared, your mind robs you of your steam and you lose yourself in the middle of all that action. At the time I competed in Jiu-Jitsu I was about 33 pounds lighter than today and I’d charge at the big guys like it was nothing. That makes a big difference – often the flow is a matter of attitude. Of course, technical and physical preparation are key. However, without attitude, you’re not going anywhere.

In conclusion, is there some crucial point to start being more dynamic in a fight?

FLÁVIO CANTO: I do not think it is a matter of timing. The nimble game is not synonymous with cartwheels and showboating. It only makes sense if you are always looking for a better fit, the submission, the win. The magic is in being dynamic the whole time, always playing offensively.

***

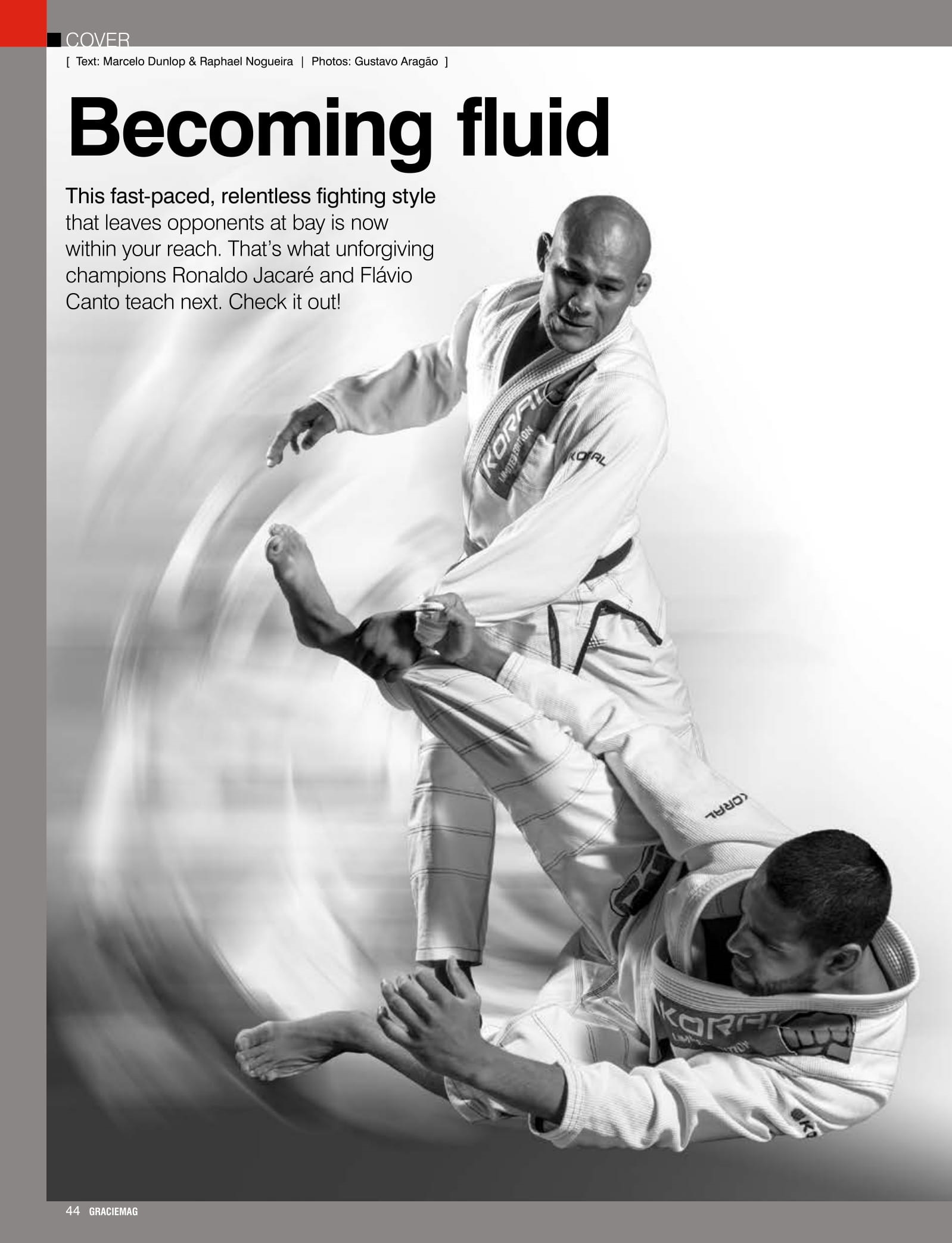

Practical guide to fluidity

Under the guidance of ace Ronaldo Jacaré, check out four efficient exercises to boost your nimbleness on the mat

Exercise 1: Jacaré props his left hand on the floor between his sparring partner’s legs, and uses it as the needle of a pair of compasses, moving his own body to the right. When he approaches control from the side, Jaca changes placement. Now it is the palm of his right hand that provides support, and he moves to the left side. This exercise must be done at the greatest possible speed. Do 20 reps – ten to each side.

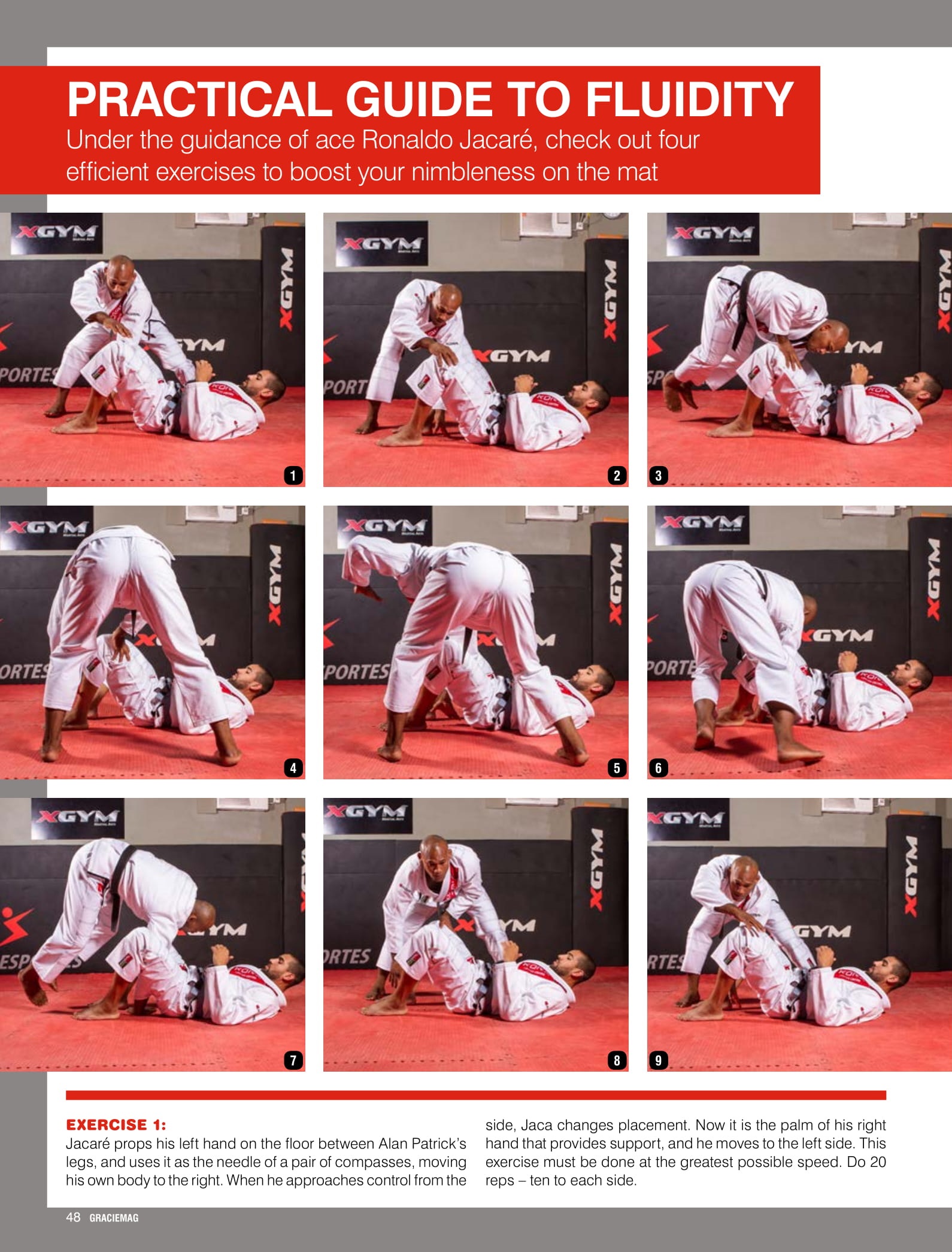

Exercise 2: Jacaré’s opponent stretches his left leg in the air and keeps the other one bent. Jacaré props his left palm on his foe’s right leg. Jacaré then uses the side of his head and left shoulder as a hook to neutralize the left leg and enable the guard pass. When Jaca approaches control from the side, his opponent changes the positioning, lifts his right leg and keeps the left one flexed. Jaca executes the movement to the other side, always seeking the highest possible speed. Do 20 reps – ten to each side.

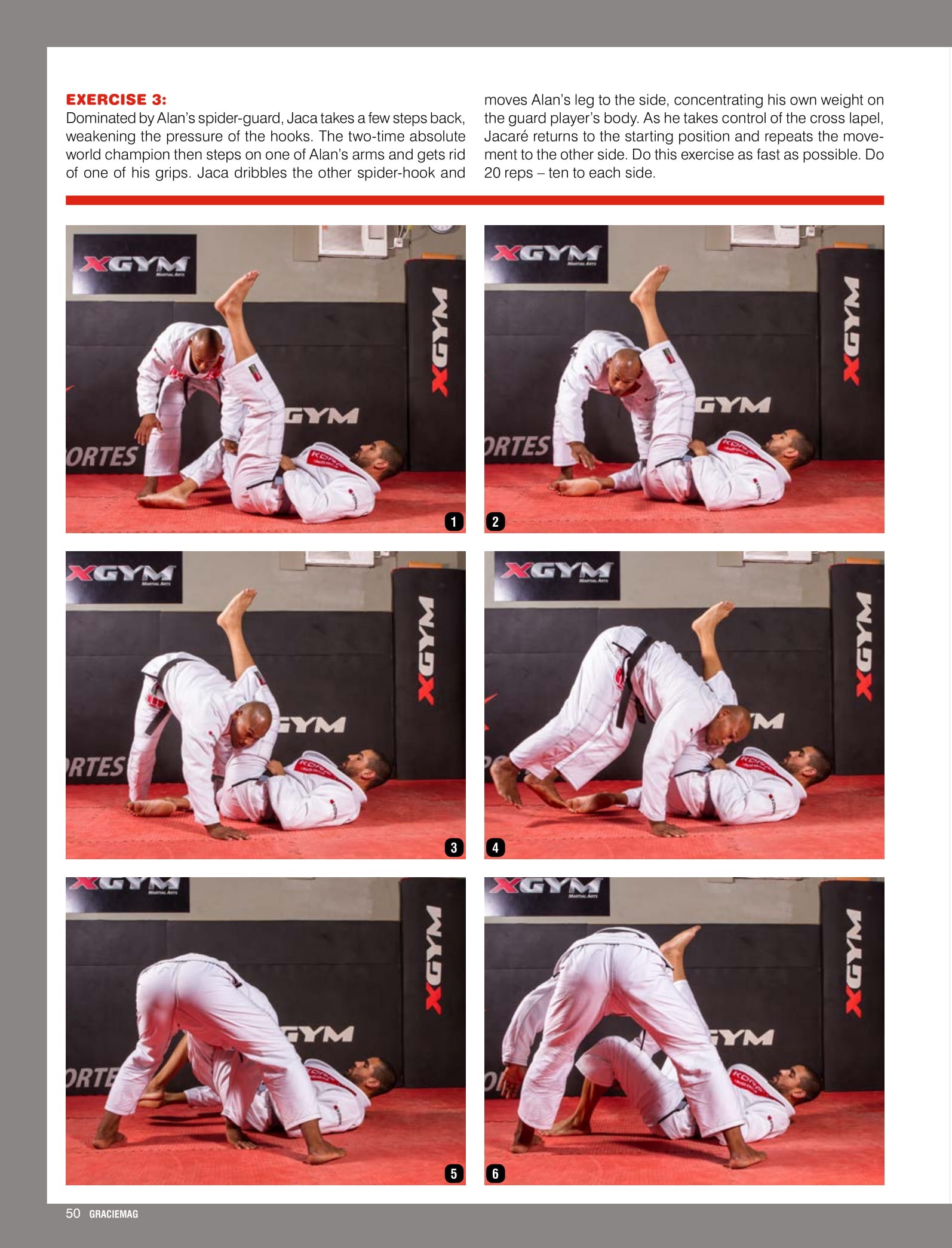

Exercise 3: Dominated by a spider-guard, Jaca takes a few steps back, weakening the pressure of the hooks. The two-time absolute world champion then steps on one of his adversary’s arms and gets rid of one of his grips. Jaca dribbles the other spider-hook and moves his opponent’s leg to the side, concentrating his own weight on the guard player’s body. As he takes control of the cross lapel, Jacaré returns to the starting position and repeats the movement to the other side. Do this exercise as fast as possible. Do 20 reps – ten to each side.

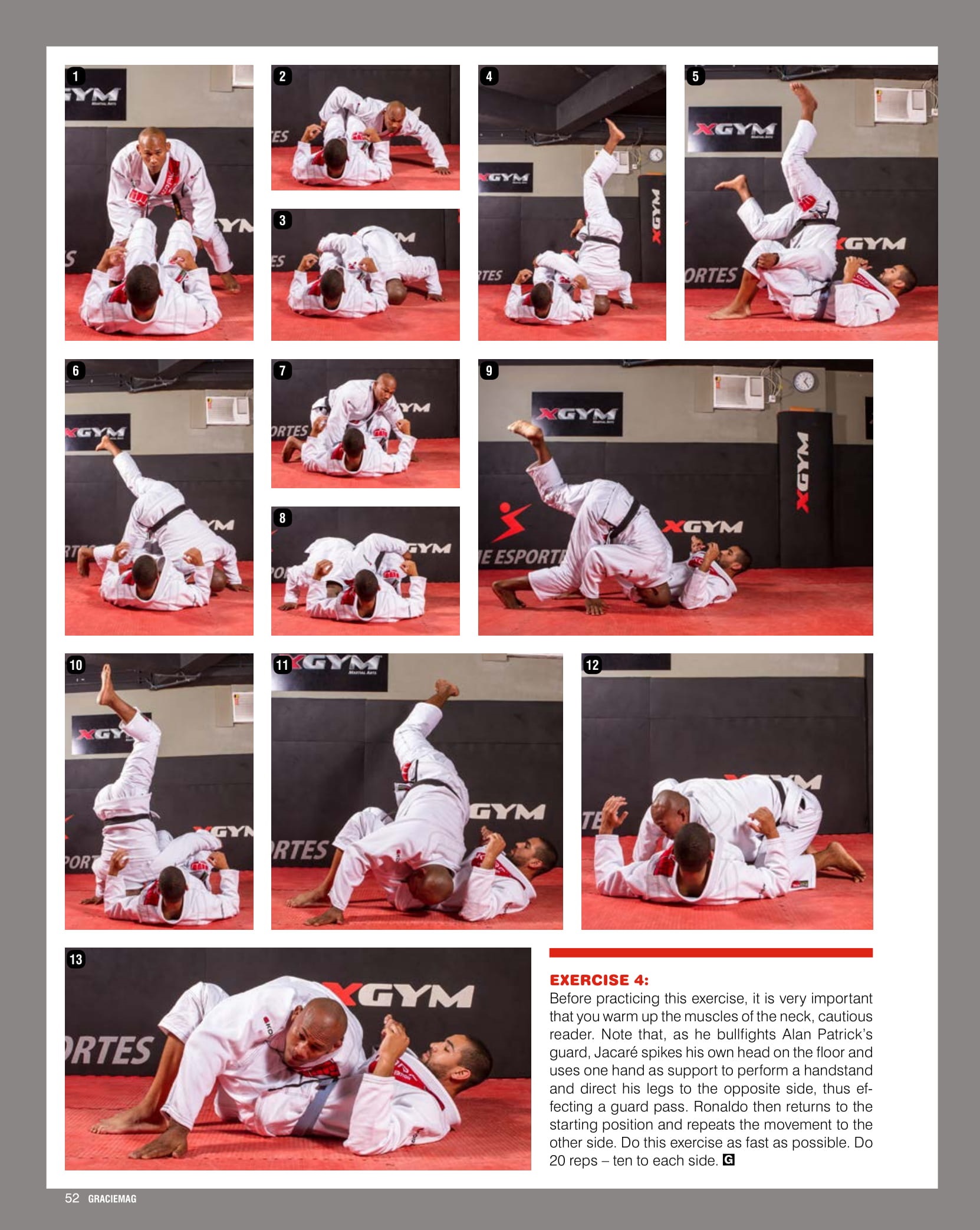

Exercise 4: Before practicing this exercise, it is very important that you warm up the muscles of the neck, cautious reader. Note that, as he bullfights his sparring partner’s guard, Jacaré spikes his own head on the floor and uses one hand as support to perform a handstand and direct his legs to the opposite side, thus effecting a guard pass. Ronaldo then returns to the starting position and repeats the movement to the other side. Do this exercise as fast as possible. Do 20 reps – ten to each side.