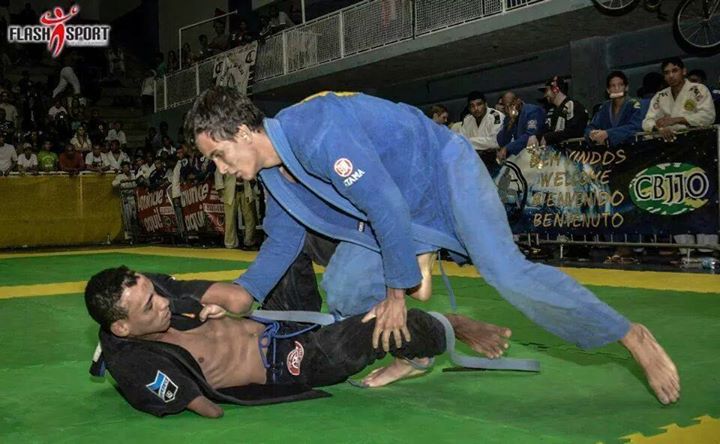

Luciano competing in Brazil. Photo: Flash Sport

One of the beautiful benefits of Jiu-Jitsu is that everyone can gain something from training–even those with disabilities. It’s not uncommon to see people with disabilities in academies and competitions and each time, they serve as a strong message that limitations are imaginary.

For the World Championship this year, one blue belt from Brazil will travel to Long Beach, CA for his chance to compete and take up an opportunity he thought he’d never have. Elena Stowell, who wrote the book Flowing With The Go: A Jiu-Jitsu Journey of the Soul about how Jiu-Jitsu helped her recover from the death of her daughter, found out about this particular blue belt and has decided to share his story.

Learn about Luciano and the disabilities that don’t prevent him from training and competing:

“I was introduced to Luciano by my friend Jean in 2012. At the time, Luciano was a young man who touched Jean’s heart with his story, his pride, and his dedication to the sport they shared, Jiu-Jitsu. I too, would be touched by these attributes.

In 2012 Luciano was training Jiu-Jitsu in a tattered karate gi. Jean made a connection with Hyperfly and they donated a new gi for him to wear. Luciano competed in this gi during the September 2012 Copa BJJ tournament. The Carly Stowell Foundation provided support and sponsorship for this tournament. Over 350 children from the Projetos Social in Rio were able to attend.

When I returned to Rio de Janeiro in August 2013 I was reacquainted with Luciano. We trained together at Top Brother gym in the municipality of Meier. Here is more of his story:

Luciano hails from Japeri, a neighborhood in southeast Rio de Janeiro. He describes his situation there as “poor, small and difficult”. The Japeri favela atmosphere is violent and bears the unfortunate stigma, in Luciano’s words, of being “the most miserable municipality with the most AIDS”.

To train at the gym in Meier, Luciano travels two and a half hours by bus. He has been training for four years and is currently a second degree blue belt. Luciano has one of the most ferocious guards I have encountered. He is a tenacious grappler despite having no arms below the elbow. For years, Luciano’s disability kept him from participating in the common activities that kept his peers engaged throughout the day. Jiu-Jitsu found him when he went to watch a friend train. Master Cezar Guimaraes (Cashquinha) had developed a project in Japeri to keep children and teenagers off of the streets. Luciano, with little else to do, went along to watch his friend, but shied from participation because he was ashamed of his scars and missing limbs. One day his friend dragged him onto the mat and started to play-grapple with him. His friend showed him what it felt like to train. Luciano was hooked. He began training and never looked back.

For a long time, Luciano didn’t look forward. He was disabled at a very young age and he had always known life to be difficult. Luciano was four months old when his mother left him in the care of his alcoholic grandfather. That evening there was a power failure and his grandfather, who had been drinking, lit several candles in the home. Luciano was sleeping on a cot when a candle fell over and started a fire. His grandfather ran from the home and was too drunk to remember that Luciano was in the cot. Luciano had third degree burns on his arms and serious burns on his head. His arms were amputated at the elbow.

Luciano’s family generates a meager income reselling fruit and vegetables in their neighborhood. The Brazilian government provides a small family benefit by way of the social program Bolsa Familia–the equivalence of $35 USD per month. In February 2011, 26% of the Brazilian population received assistance through Bolsa Familia. Brazil has a program for persons with disabilities, The Continuous Cash Benefit Programme (BPC, Beneficio de Prestação Continuada), however Luciano does not receive any funds through this program. Why he does not receive benefits through this program is unknown to me, but dissemination of information about this program is said to be a weak point. The number of steps a recipient must go through to be approved also appears cumbersome.

Despite the daily challenges Luciano faces he maintains a positive attitude. Where he once would not run shirtless in the street or go without a hat and show his scarring, he now does many things “like a normal person”, such as play soccer and ride a bike. He expressed his attitude this way: “Every day I have respect for everyone, no matter who, especially for children. I want to show that people with disabilities, there is no difficulty they cannot do.”

During my visit in August 2013, Jean and I presented Luciano with a small backpack of clothes: Jordan basketball shorts my sons had outgrown, a pair of Nikes and some t-shirts. He was stunned and appreciative, thanking us over and over again. The look on his face after he asked, “I can keep the bag?” and we smiled and said, “Yes, of course”, is one of my fondest memories of the trip. To help someone who is genuinely grateful and who finds joy in the community of Jiu-Jitsu was an honor for us.

Luciano’s goals are not unlike those of any Jiu-Jitsu competitor, “to be a champion”. He has already placed second and third in tournaments. The barriers people place upon him are motivation to succeed. “Many people think that I am not able to give all my best, but I can show in the way I train that one day I can achieve my goal to be a champion.”

According to the International Disability Rights Monitor’s 2004 Regional Report of the Americas, 30% of persons with disabilities receive less than the minimum wage in Brazil. About 80-90% of persons with disabilities are unemployed or outside the work force. Most of those who have jobs receive little or no monetary remuneration as recorded in “Disability and inclusive development: Latin America and the Carribean” by World Bank.