[First published in 2008. Scroll down for plain text.]

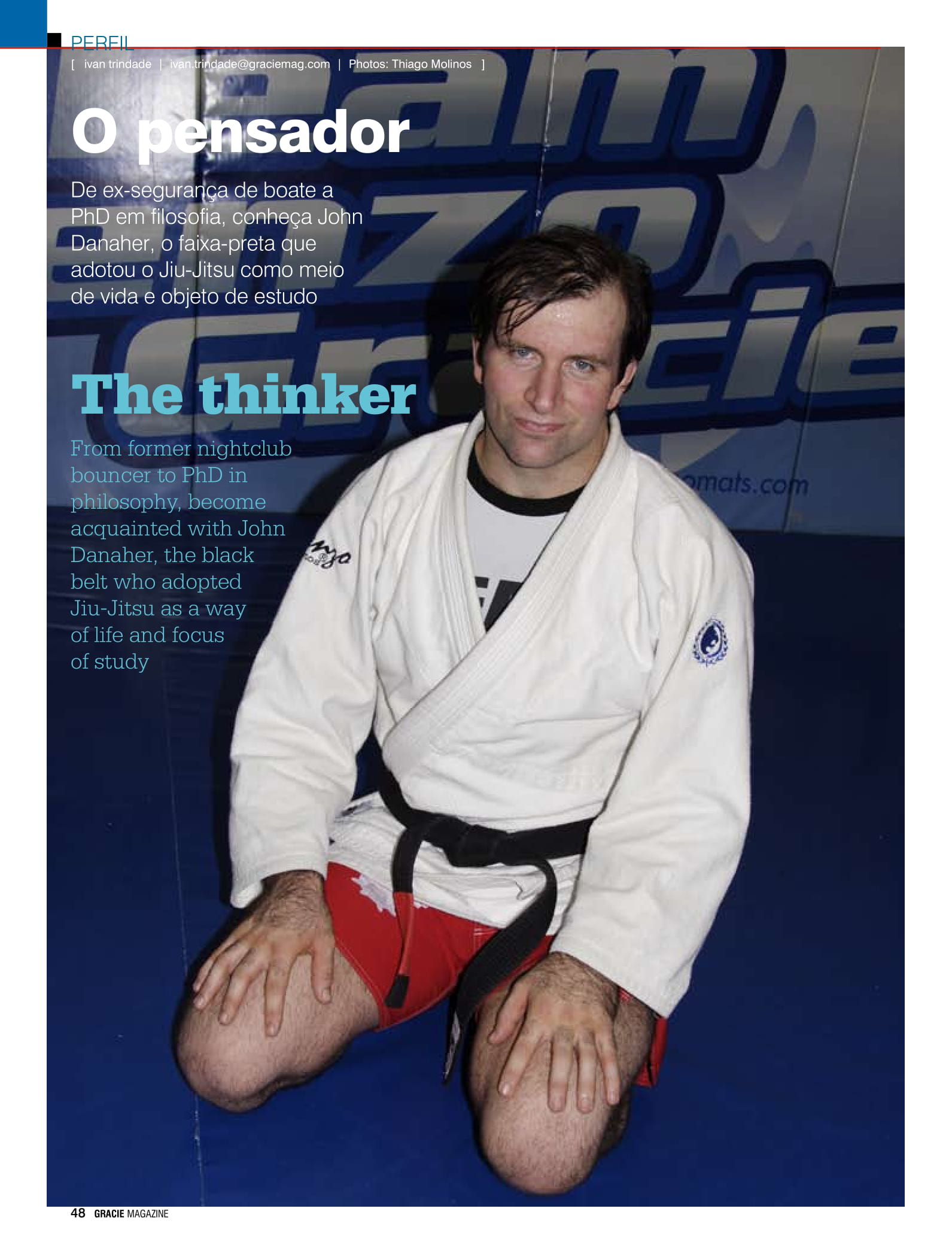

A visit to Renzo Gracie’s

academy means, almost

certainly, meeting

the character in

this profile. Every time we tried

to reach John Danaher for an interview,

he was either finishing

or starting a class. “I trust John

completely. I know I can leave

the academy with him and not

worry, the students will be in

good hands for sure,” says boss

and friend Renzo. Such trust is the

fruit of over ten years of friendship:

“One day a friend told me about

these crazy Brazilian wrestlers

who focused on wrestling on

the ground and who would challenge

anybody and who won all

kinds of crazy no-rules fights. I

was curious, even more so when

I saw UFC 2 where Royce Gracie

demolished a bunch of very tough

looking opponents with little apparent

effort. I began training under

Renzo Gracie and his partner

at that time, Craig Kukuk. Renzo

had just moved to NYC,” relates

Danaher. Renzo talks of his memory

of the first days: “John arrived

here in the gym’s very first year,

towards the end of 1996. He was

a weight-lifter. He was studying

at Columbia University and

worked at the door in nightclubs

for a living. As soon as he started

training, I realized he was very

intelligent, but in the beginning

he would get injured a lot, due

to the excessive weight lifting

he’d do.”

In Renzo’s memory, there

are three elements that stand

out in the biography of the now

black belt. American by birth (1),

Danaher was brought up by his

diplomat parents in New Zealand

(2), where he stayed until he

was accepted at the Columbia

University School of Philosophy

(3), in New York. On the country

where he spent his youth, Danaher

has fond memories: “New

Zealand is a nation where sports

are strongly emphasized and like

most children there I played as

much rugby, soccer, swimming,

running etc. as I wanted. Unfortunately

I badly dislocated my knee

as a child and a disastrous knee

operation permanently crippled

one of my legs, an event that

shut out most athletic activities

for me. For awhile I devoted myself

solely to intellectual pursuits

but the body’s natural demand

for physical release kept pushing

me towards some kind of outlet. I

began kickboxing but my physical

limitations made that very

difficult. I began weight training,

since most of the exercises isolated

certain muscle groups and

did affect my leg. In a short time

I began to get much bigger and

throughout my university years

in New Zealand I lifted weights

almost every day until I ballooned

up to well over 100 kilos.”

Wary of taking a licking

Strong as an ox and finishing

his studies, Danaher decided

to return to the land of his birth.

Accepted into the Columbia

philosophy department, he went

to live in New York. He soon

discovered that his scholarship

would not be enough to live on in

the “Big Apple”: “I got work as a

bouncer. This was a job I had done

in New Zealand and I guessed

it would be roughly the same.”

Although he

had prior experience,

John

suffered some

hardships with

the differences

between the

two countries

and their people:

“I found

that Americans argue and verbally

challenge each other much

more than New Zealanders and

Australians, but physically fight

much less; however, when they

do fight, the consequences often

run much deeper. In the hiphop

clubs that I mostly worked,

fights were typically ambushes

where a group of people would

rush one person and knock him

down.” The characteristic of

the job made

John want to

learn skills that

would he l p

him to better

defend himself

during altercations,

and he

used his head:

“I found that

the intensity level of the fights

quickly put most people down

on the ground where kick boxing

skills were of little value.

Much to my surprise, the best

bouncers I worked with were

usually wrestlers, who were able

to easily take people down, while

preventing other people from

taking them down.”

Starting Jiu-Jitsu

This realization brought

him to Renzo. “I began as a very

poor student, too big, too slow,

trying to use muscle and size as a

substitute for technique. I started

late in life, around 27, and with a

crippled leg, so I did not see myself

as anything more than a part-time

student who could make his job

as a bouncer easier by learning

some takedowns, pins and

chokes. Within a very short time

I was using Jiu-Jitsu in bar room

brawls on a nightly basis and I

was greatly impressed by the degree

to which I could control very

unruly people without harming

them.” But, what was merely a

functional apprenticeship, turned

into a complete passion: “By degrees

I became more interested

in the sport. Though my physical

limitations often made Jiu-Jitsu

painful and frustrating for me to

learn, I slowly began to improve

and make some small technical

progress. I stopped lifting weights

and shrunk down to 75 kilos. I became

one of the smallest bouncers

in Manhattan which meant

that everyone thought they could

defeat me!” Along with his physical

stature, career also changed.

Around that time the main teachers

of Renzo’s academy, Matt

Serra, Ricardo Almeida and Rodrigo

Gracie left to start their own

schools. Renzo asked me to begin

teaching afternoon classes. This

enabled me to stop bouncing and

focus on Jiu-Jitsu.” Renzo enters

the conversation telling how the

transition from student to instructor

went, and revealing another

facet of his friend’s personality:

“Something

funny about

Danaher is

how his philosophy

is that

it’s not worth

working to

the point of

suffering to

accumulate

money. What

he’d do was

just to pay

the bills. I had

a talk with

him and convinced

him to not waste the most

productive years of his life. He

argued that he didn’t need money

and I responded that, if he didn’t

need it, someone in his family

would need it. So he told me his

mother wanted to buy a house. To

help his mother, he started teaching

private lessons and making

more. So he got a taste for it, and

hasn’t stopped since.”

The teacher

He didn’t just keep going,

he dove head first into his

new function, inspired by the

academic realm. “I had been a

good teacher of academics at

Columbia and now I wanted to

be a good teacher of Jiu-Jitsu. I

had the advantage of full-time

study and lots of willing partners

to experiment and theorize. As a

teacher I focus a lot on maximum

efficiency in body movement and

the idea that Jiu-Jitsu is, above all

else, the science of control that

leads to submission. Anything

that deviates away from this,

deviates away from the essence

of the sport.”

Renzo agrees with his student

and companion’s vision of

teaching: “These days, you might

find a teacher at his level, but not a

better one. He fulfills the needs of

the students perfectly. He is true

to Jiu-Jitsu’s roots and studies

the techniques a lot. Training at

the gym, he’s tapped out lots of

Brazilians.”

When the subject comes to

John Danaher, the words “studious”

and “intelligent” come up

a lot. John has studied Jiu-Jitsu

so much that he knows what the

abilities and limitations of each of

his students are. “Every student

begins the game with a certain

set of attributes. Some are blessed

with flexibility,

strength,

fitness, intelligence,

determination

etc,

etc. Possession

of these

determines

the speed

and ease with

which you acquire

the skills

of Jiu-Jitsu.

Remember,

though, that

some attributes

can negate others. So for

example, very gifted athletes often

lack staying power, just because

most things come easily to them.

When they find themselves being

repeatedly defeated by smaller,

weaker training partners, they

drift away. In the end, the speed

with which you acquire skills is

not important, just that you get

there in the end. So I theorize

that the most important attribute

in Jiu-Jitsu is staying power. You

must train consistently for a long

time and your game will develop

in accordance with your natural

attributes.”

For someone with such clarity

of vision, predicting what is to

come is not such a tough task.

Danaher foresees a division between

students of Jiu-Jitsu in the

future, and this separation has a

lot to do with MMA: “In the future,

Jiu-Jitsu students will fall into two

types: those who study only the

sport of Jiu-Jitsu, just because

the sport appeals to them in some

way; and those who study Jiu-

Jitsu as part of a comprehensive

MMA program, where Jiu-Jitsu

is one essential part of what they

do. As a teacher of Jiu-Jitsu I have

to be able to help either kind of

student. My never changing goal

is thus to keep abreast of new

developments and trends in the

sport, along with the all-important

fundamentals and learn them as

thoroughly as possible so that I

may convey them to my students

in the best possible manner.”