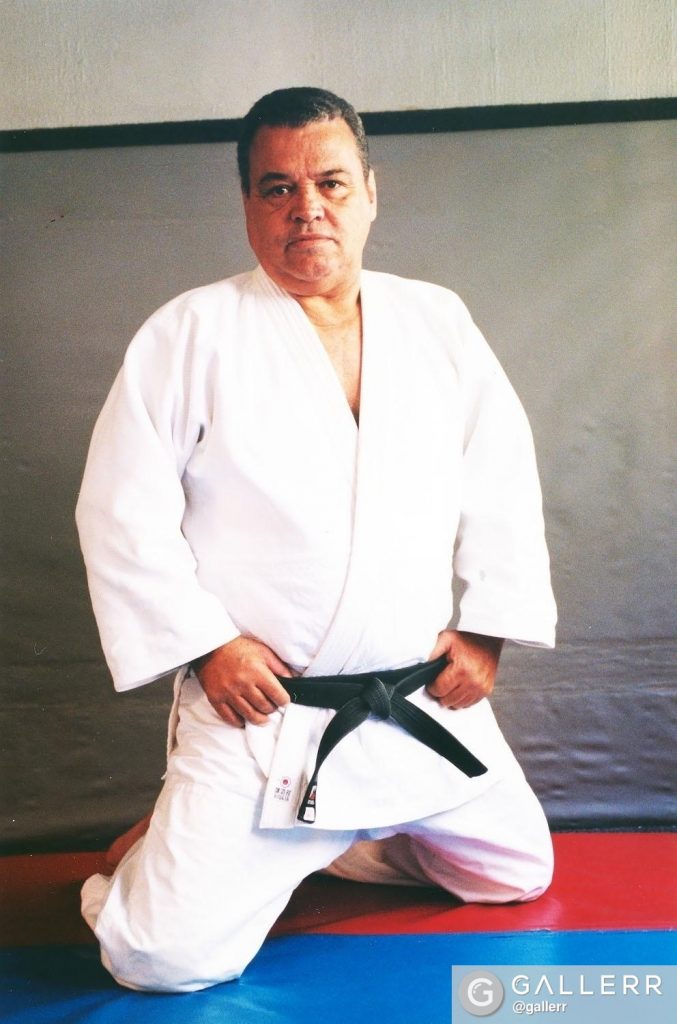

Carlson in 1955. Agência O Globo

[First published in 2006.]

More than broken records, Carlson had empathy and a lot of lore to him — a combination capable of preserving the work of the eternal boy that captivated everyone and lived as he wished.

He used to lie about his age and dye his hair. That aside, Carlson was completely authentic and truthful. He’d always say what was on his mind and would never hold his tongue in order to prevent a conflict or to sound politically correct. On the contrary, he used to create slang that made his points of view even more clear and powerful. The “creontes” know that very well.

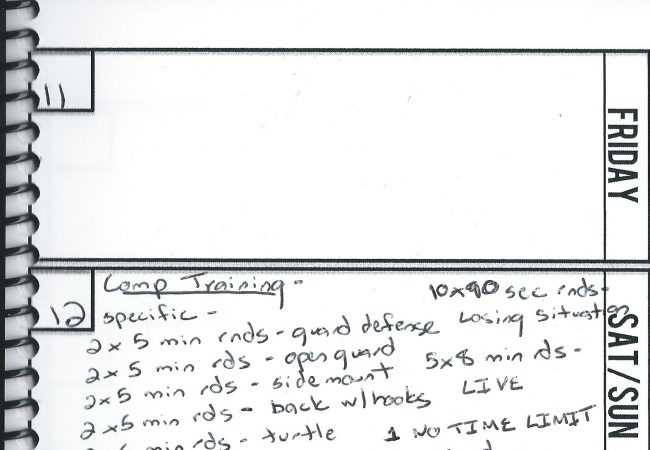

Carlson had a caring heart that would make him a complete failure as an administrator. He would distribute studentships for his pupils in the same number of the titles his academy would win. Carlson is by far the biggest winner in jiu-jitsu’s history.

His heart at times seemed too big for his own good. Many times he was taken advantage by pupils. “I’d always tell him: ‘Master, a lot of people are exploiting you. That way, you will die with nothing.’ He would answer: ‘What’s the problem? Won’t I be dead anyway?’”, remembers pupil Marcelo Saporito.

Carlson acted like a king that made no distinction between poor and rich. Saporito swears that for a long time Carlson would bring a group of beggars to shower and sleep inside his gym. At the same time, he was adulated by politicians, scholars and millionaires without ever developing any feeling of superiority.

“He was very happy, lived his life as he wished, detached from material values and cheap worries. No doubt he takes with him many stories of victory and joy“, says one the first black belts trained by Carlson, Fernando Pinduka. By the way, what would Carlson like to take to heaven besides his stories?

We can start our list by that bag he would always carry around his waist, ignoring if it was fashionable or not: “In that bag you would always find a hair brush, a phone book and a camera”, reveals the great friend Osvaldo Paquetá. There you go. Another thing he would love to take with him: the camera. “I’ve never seen anybody take so many pictures as Carlson. It was impressive”, remembers pupil Wallid Ismail. Something else that cannot be out of the list is a fight cock (“But no cowardly cock!”, he must be screaming from heaven), although there’s a rumor that cock fights are forbidden in heaven.

What else is there? Bolero and French music records? Playing cards, which he loved doing? A dictionary for him to defy the saints with his knowledge of the language? Saporito remembers something more simple, a top that master would pin on the mat of his academy every training break: “His eyes would glow. ‘See, I had a good childhood’, he used to say. I’d reply: ‘You never left childhood. You are a nothing but a grown child’”, remembers Saporito, almost in tears.

Nevertheless, it is probable that Carlson would exchange all those items for being with his good friends and the women he loved for a few more hours. “He was the kind of person that was not able to live alone”, says Paquetá. But you can always find good company in heaven. Carlson is probably training now with other immortals of jiu-jitsu, including his father Carlos, his brother Rolls, the most talented disciple, Serginho de Niterói, and Valdemar Santana, the rival he admired.

1956: Versus Valdemar Santana. Agência O Globo

His own rules

Brilliant but ill-tempered, Carlson would easily cave in to a fatty, sugary mix of açaí and guarana syrup, despite having diabetes and high cholesterol. Paquetá says that Carlson would sometimes hold in his gut to disguise the extra pounds that he had gained since he quit being an athlete and became a trainer.

Whenever he felt not so good, he would go back to the Gracie diet, just like a kid that just misbehaved and acts really well until things settle down. That happened all the way to his last days. Paquetá reveals a phone call he received from Carlson. “He called me and said he was in a lot of pain but assured me everything would be alright because he was taking really good care of his eating.” That was not enough that time. He needed a medical intervention right way, which only happened later, when his condition was already critical. Stubborn to the last degree, Carlson was afraid of hospitals. Whenever someone advised him to go to the doctor, he would say: “Are you putting a curse on me?”

He would even hide from his family his health problems. Maybe because he didn’t want to admit that the undefeated MMA phenomenon of the 50s and 60s was getting old. Or maybe because of his keen sense of self-confidence that made him believe he had an inner force that would keep him away from all of life’s dangers. That’s probably why he allowed a simple kidney stone to evolve into a septicemia that stopped his heart at 6 a.m. on a cold morning in Chicago.

Carlson’s death made it obvious that his legacy will be preserved forever. The commotion caused by it made clear the importance he had in the jiu-jitsu and MMA world. More than 500 people attended his seventh-day mass in Copacabana, Rio de Janeiro. Friends and enemies, followers and rivals all got emotional. Robson Gracie, his brother, defined the moment in words: “Whenever an angel goes to heaven, he gets people together. I’m certain that Carlson will never be forgotten.”