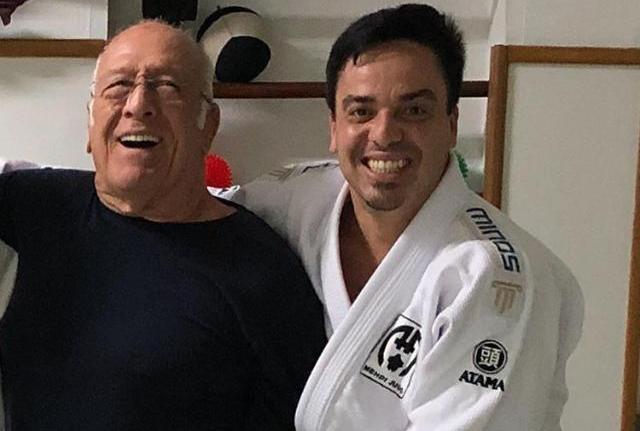

Master Georges Mehdi (1934–2018), who died six months ago in Rio de Janeiro, left behind many good memories, lessons, and a slew of tough students spread across Brazil’s mats.

One such student is Marcos Ayala, a teacher at Minos Funcional Fight in Rio, who is a black-belt under Muzio De Angelis and studied judo under Mehdi. The Cannes-born sensei’s gym is still going, led by family members and students.

Ayala agreed to share with Graciemag readers the chief lessons he absorbed in the classes taught by the red-belt Mehdi, a silver medalist at the 1963 Pan-American Games.

GRACIEMAG: What is the most valuable lesson you learned from Sensei Mehdi?

MARCOS AYALA: I trained with Sensei Mehdi for seven years, and I feel the biggest lesson I learned, without a doubt, was looking at others. He was able to care for his students like they were his own children. Technically, he was the teacher with the most knowledge I’ve ever met. He had a deep, special preoccupation with the details of each move taught.

Many judo stars don’t forget the first lesson in humility given to them by Mehdi: to take good care of the school and even clean its bathroom. How did that go?

It happened, but it wasn’t done only in the bathroom; we always took good care of our dojo. So we would clean the bathroom, the mat, the reception and all other parts of the school. In Japan, one of the traditions in kids’ schools, and also martial arts dojos, is soji, which just means “to clean.” At Japanese schools, soji no jikan is cleaning time — that is, the time the kids pick up the cleaning materials and give the school a good cleaning. In general, it’s 15 minutes a day at the schools, and each kid has a cleaning group, with one leader.

And what did you learn from this Eastern tradition?

In the act of soji, the act of cleaning, we learn how to clean our ego, we learn how to be more humble and “throw out” our filth and imperfections. And we would also learn to meditate on the training, reflecting on what we got wrong and right, to seek evolution. Soji is more than a physical cleansing, but an educational act of spiritual cleaning. It’s a way of working on your respect for your neighbor.

What other good stories do you remember about him?

We had the habit of meeting beyond judo classes, with frequent encounters in restaurants where we always exchanged ideas and heard the stories of Sensei Mehdi. It was a pleasure just to be sitting next to him listening to those stories and teachings. Both his feats as a competitor and the stories he lived as a teacher. No doubt the stories he lived in Japan are the best. He lived for 12 years in the cradle of judo, and said that in the beginning he was discriminated against at training. Then he gained respect from the Japanese, for having a very efficient move (de ashi barai), among others. And he also earned respect for never shying away from a good cleaning, the soji. With an always irreverent and very solicitous demeanor, he became very friendly with Sensei Okano, a Japanese phenomenon with whom he maintained contact until the end of his life.

How do you think Mehdi’s teachings shaped your style of fighting and teaching?

The sensei was always much more than a simple judo teacher — he was a teacher of life. He had an enormous ease in reaching the hearts of the people who surrounded him. It was not difficult to be enchanted by him. Today I have two children, and I feel that I bring home many things that I have experienced and learned from Sensei Mehdi, and I use this a lot for their education. From establishing rules at home and being serious about following them, to the caring and tenderness for the person who is by your side.